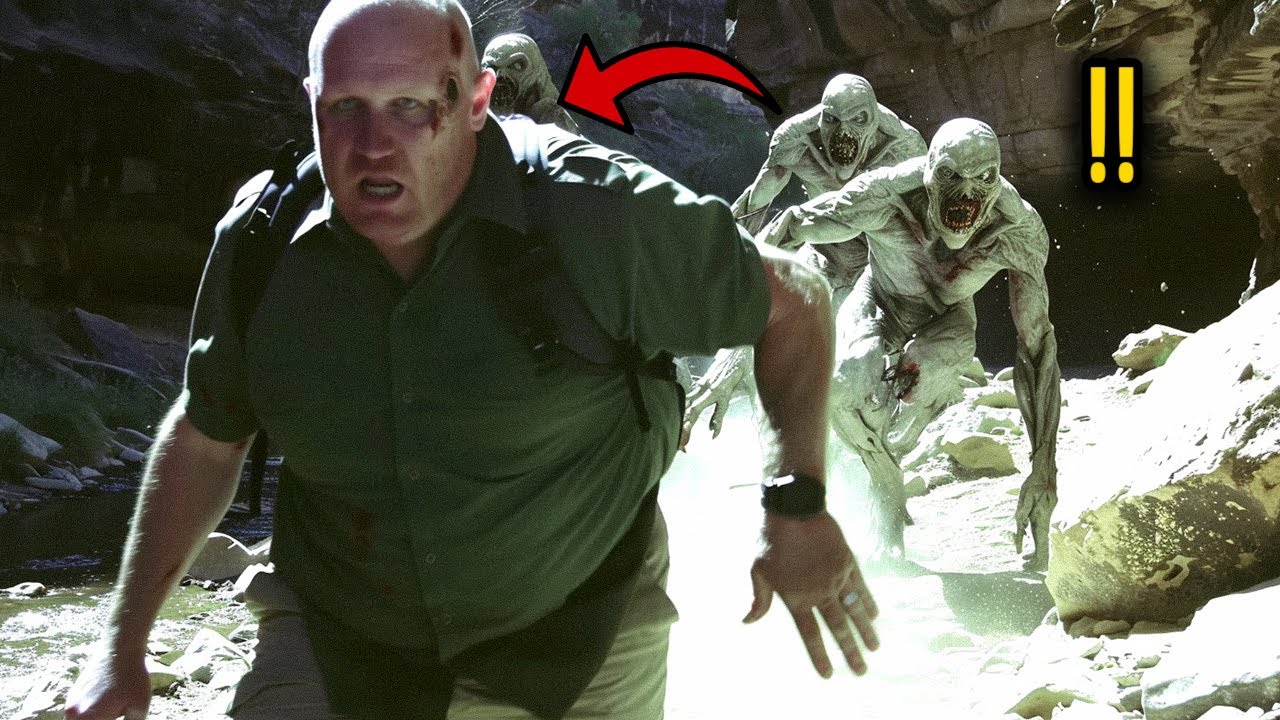

The Grand Canyon of Arizona is not just a natural wonder, a monument to geology and the vastness of time. For many, it is sacred ground. For others, it is a fountain of tourist wealth. But for a small group of people, it hides a dark, terrifying secret that defies both logic and science. A secret so disturbing that authorities have silenced witnesses, destroyed evidence, and sealed tunnels—everything to protect the façade of a multibillion-dollar industry. What follows is not a work of fiction, but a chilling record of encounters that shook even the most seasoned rangers, proof that beneath the majestic beauty of this place, something unknown—and hostile—lurks.

The incidents, though years apart, follow a haunting pattern. Three cases across 14 years, three different types of creatures, yet all pointing to the same conclusion: the Canyon harbors something that should not exist.

The Jualapay Trail Incident: Aerial Shadows and Nightmarish Claws

The first story took place in the summer of 1988. Ranger Jack Morrison, a veteran with 23 years of service, faced a scene that fit no category he knew. On June 23, an emergency call drew him to the Jualapay trail. A group of seven tourists had camped at lookout four, two miles from the main trail. By dawn, only five were still alive.

When Morrison arrived, the campsite was a picture of chaos. Tents shredded, sleeping bags torn open, supplies untouched. The scene didn’t match any known bear or cougar attack. The survivors, trembling and in shock, had hidden in a rocky crevice. One of them, Sara Lynch, a nurse from Denver, gave a trembling account. Around midnight, scratching sounds began. What they thought was a small animal turned into something much more sinister.

Sara and her husband, Tom, saw three towering figures—nearly eight feet tall. Humanoid shapes with grayish, translucent skin, unnaturally long arms, and sharp claws instead of fingers. Their elongated faces bore hollow sockets where eyes should have been. They moved in jerky leaps, grotesque like puppets. Mike Rodríguez, a programmer, was dragged straight from his sleeping bag. His girlfriend, Jen Martínez, ran after him—both vanished over the edge of a 1,300-foot cliff.

The most chilling discovery came later. Tracks on the soft ground looked like oversized human handprints—one and a half times larger—with claw marks. They led straight to the cliff’s edge, then stopped, as if the creatures had leapt into the void.

The bodies were never found. Only scraps of clothing and Mike’s backpack turned up downstream in the Colorado River. Local Havasupai guides refused to join the search. Through an interpreter, elder Thomas Sikuaya explained: “This place has been cursed since ancient times. The Tall Men live here—the spirits of those who broke the taboo. By day they hide in the deep earth. By night, they hunt.”

Park authorities labeled the case a “fatal accident.” Witness testimonies vanished from the official report. Morrison later admitted he had been ordered to stay silent—stories of “monsters” would harm tourism. Survivors were told to forget what they saw, with thinly veiled threats from plainclothes men claiming to work for the Department of the Interior.

A month later, geologist Helen White stumbled upon a cave filled with human bones stacked like offerings. The bones bore teeth marks larger than any human’s. Among them lay Mike’s driver’s license and Jen’s wristwatch. Cameras and flashlights failed inside the cave, while scratching noises echoed from deeper within. Authorities later sealed the entrance with explosives, declaring the area “hazardous.”

The South Rim Incident: Red Eyes and the Hunt in Packs

Seven years later, in 2005, terror returned—this time at South Rim. A group of six tourists from Minnesota, led by war veteran Robert Haynes, camped outside the designated zones. The first warning signs were glowing red lights in the bushes. Eyes that didn’t blink.

One creature—massive as a bear but upright like a man, with an elongated snout and burning red eyes—dragged Kevin Black into the darkness. His scream cut off abruptly. Survivor Steve Olsen described the horror: Haynes fought back but was thrown several yards with ease. Half an hour later, the creatures returned—not one, but many. A dozen red eyes encircled the camp. The group was torn apart, one by one. Olsen survived by squeezing into a narrow rock cleft, watching helplessly as the creatures carried his friends away.

When Morrison investigated, he recognized the signs. These were the same beings—but more organized, as though they had learned to hunt humans. Tracks led to a hidden cliffside cave. Inside, the stench of rot and urine was overwhelming. Bones of humans and animals were scattered with predator bite marks. At the deepest point lay a nest, filled with victims’ belongings dating back decades.

The team discovered a tunnel extending further. Thermal cameras picked up moving figures. The air grew hotter, with dangerous levels of carbon dioxide. Growls echoed from all directions—an entire pack closing in. The rangers retreated.

That night, hidden cameras captured towering bipedal figures entering and exiting the cave. One stopped, staring directly into the lens—its eyes glowing with intelligence. Then the cameras went dark—not destroyed, but deliberately disabled. As if the creatures knew.

Once again, the cave was sealed. Once again, survivors silenced. Olsen tried to go public but was dismissed as a crank.

The Colorado River Incident: Silence and the Evolution of Fear

Thirteen years after South Rim, the Colorado River itself became the stage of horror. A rafting expedition of 15 people, led by veteran guide Dave Thompson, encountered what may be the deadliest episode yet.

According to Havasupai elder Sikuaya, the “Tall Men” are growing bolder. Once, they feared fire and noise. Now they are many—and they no longer fear humans. His tribe’s legends tell of fertile valleys abandoned when the creatures hunted openly. The knowledge of how to fight them has been lost. “The whites,” he said bitterly, “refuse to believe.”

The stories of Morrison, Olsen, and now Thompson paint a chilling picture: these predators are not only real, but evolving—becoming smarter, more daring, more numerous. They don’t just hunt for food. They seem to have a plan.

What are they? What do they want? No one knows. But one fact is certain: they exist. And the official silence—far from protecting tourists—places them in mortal danger.

The Grand Canyon hides far more than the glossy brochures admit. And what lies hidden is learning to step into the light.

News

The Final Whisper: Leaked Video Reveals Star’s Haunting Last Words and a Secret That Shook the World

The grainy, shaky footage begins abruptly. It’s dark, the only light coming from what seems to be a single, dim…

The Nightmare in Lake Jackson Forest: An Unhinged Individual, a Brutal Crime, and a Bizarre Confession

On a cold December day in 2022, a 911 call shattered the usual quiet of Lake Jackson, Georgia. A frantic…

The Vanished Twins: 20 Years After They Disappeared, A Barefoot Woman on a Highway Reveals a Story of Survival and a Sister Lost Forever

The world moved on, but for Vanessa Morgan, time stood still. For two decades, she lived in a ghost town…

A Chilling Grand Canyon Mystery Solved: The Hiker Who Returned from the Dead with a Terrifying Tale

The Grand Canyon, a majestic chasm carved by time, holds secrets as deep as its gorges. For five years, one…

The Pyramid’s Ultimate Secret: A Leaked Photo Reveals Giza Is Not a Tomb, But Something Far More Profound

For 4,500 years, the Great Pyramid of Giza has stood under the scorching Egyptian sun, the last survivor of the…

The Loch Ness Monster: Unmasking the Deception, The Science, and The Psychological Truth Behind an Immortal Legend

Could it be that everything you’ve heard about the Loch Ness Monster is a comfortable bedtime story, a simplistic tale…

End of content

No more pages to load